“To Shrive Clean the Hearts of Men”: Adaptations of Pilgrimage and Sainthood in Elden Ring: Shadow of the Erdtree

- Alex Heath

- Jul 6, 2025

- 24 min read

I. Introduction

FromSoftware’s single-player roleplaying game Elden Ring (2022) takes place in a medieval fantasy world called The Lands Between developed in conjunction with George R.R. Martin, drawing on aesthetics of the period as has become tradition in the fantasy genre. Among the myriad of borrowing that Elden Ring did from the period come depictions of divinity through the royal characters who make up many of the bosses faced within the game, Queen Marika and her bloodline. In particular, her son Miquella, who is born cursed with eternal youth and blessed with the power to charm others.[1] In the Downloadable Content (DLC) add-on to the game, Shadow of the Erdtree (2024), Miquella becomes the focus of the story as he seeks to attain godhood for himself. It is in this addition that Elden Ring and Shadow of the Erdtree provide a reimaging of medieval sainthood to a modern audience with the character of Miquella and the use of pilgrimage as a narrative and ludic structure of the game. To elucidate this point, this argument will move through several phases: 1) an overview of the game itself and the DLC, 2) delving into the practice of pilgrimage and the culture around it from a medieval and early modern standpoint, 3) the precedent of medieval sainthood that can be seen in Miquella found in the Old English poem Andreas, and finally 4) a discussion of spatial narrative and storytelling as it relates to both Shadow of the Erdtree and Andreas.

II. Elden Ring and Shadow of the Erdtree

Elden Ring adheres to a medieval fantasy aesthetic, though with a darker twist. Rather than coming into a story full of characters as one might expect of the Tolkien-descended adventure fantasy, characters for the player to interact with a few and far between, and very little of the story is exposited to the player as a result of there being few characters to interact with. Similarly, while many games proactively give the player information to push forward on their journey, Elden Ring delivers information about the world and the plot primarily through the descriptions of items or through the environment that the player is able to explore freely.

This obtuse approach to storytelling produces an investigatory experience, where the player must seek out the information of the story to make sense of it within the game as well as—for some players—outside of it on YouTube or encyclopedic sites like Elden Ring wikis. A seeking out of the story in place of it being paced out and placed out clearly for the player may seem daunting, asking the player to put forward a significant effort towards understanding the narrative experience which in many other games takes primacy over gameplay—or ludic—elements. In games like Life is Strange (Don’t Nod, 2015), Layers of Fear (Bloober Team, 2016), and Dear Esther (The Chinese Room, 2012) for example, the story acts as the motivating force for the player. The goal of these games is to progress the story and watch as it unfurls, with very little mechanical challenge or engagement. Rather than asking for the player to master a set of skills to overcome in-game challenges, these titles are lumped together with the title of “walking simulator”, a typically derogatory term used to assert that these games are not interesting to play because the only actions the player can take are moving through the environments and looking at objects. What this kind of limited gameplay reflects is a greater interest in actions of looking, movement, and paying attention to the story in a way that is not dissimilar to watching a film. Elden Ring, however, does not take the walking simulator approach to its secret story.

Instead, FromSoftware is known for its punishing difficulty, lack of difficulty setting, and avoidance of tutorials, preferring instead to thrust players into the game to learn through brutal failure. The gameplay of Elden Ring is a challenge to learn and then apply to taking on the bosses within the game, requiring management of resources in time with attacks during split-second windows between enemy attacks to retaliate. Should the player fail in a combat encounter, they are sent back to a safe place—Site of Grace, as the game calls them—and lose all of their resources which are necessary to increase the power of their character, presenting every engagement with an enemy as a high-stakes challenge. Robinson et al. observe in their study on the appeal of this difficulty level that, “intensely difficult games like Elden Ring can produce equally intense feelings of inadequacy, which can only be ameliorated by becoming adequate to the challenges they present. . .One way scholars have understood the role of difficulty in video game design is through Csikszentmihalyi’s (1997) concept of flow, which occurs when an activity (e.g., gameplay) strikes a balance between challenge and skill.” (3-4). This balance between challenge and skill is exactly how Elden Ring is able to engage players both mechanically and narratively, since both require skill to overcome challenges to their respective progressions. In their conclusion, they go on to remark that “to play Elden Ring is to lodge oneself in the unevenness, to strategize around it, to manage one’s feelings in response to it, and to make sense of its strange, some might say perverse, appeal,” something that is not dissimilar to the narrative environment that the characters inhabit within the game itself (Robinson et al. 16).

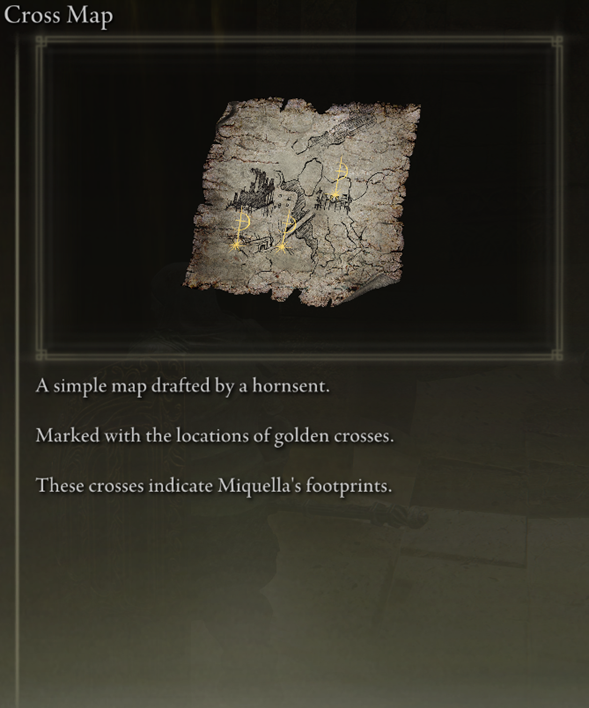

Shadow of the Erdtree is the expansion to Elden Ring, taking the player into a new area of the in-game world—The Shadow Lands—to follow Miquella who is in pursuit of godhood. To achieve his apotheosis, he enlists a cast of characters to assist in his goal to “make the world a gentler place” and follows in the footsteps of his mother, Marika, to usher in an “age of compassion” by “abandoning everything—his golden flesh, his blinding strength, even his fate. All in an effort to bury the original sin. To embrace the whole of it, and be reborn as a new god” (Elden Ring). In order to truly ascend to godhood, Miquella sheds every part of himself literally and physically before the ascension can be complete; pieces that the player is tasked to find in order to learn how to stop Miquella from bringing about his age of compassion. At each instance where Miquella shed a piece of his being, there are crosses of light that he left to memorialize what was left at the various locations.

Exposited by Sir Ansbach, one of the characters originally in league with Miquella as the player gives Sir Ansbach additional details about the crosses they have come across during their pilgrimage through the Shadow Lands, “he is bound for the tower of shadow. And that is where he intends to rise to true godhood… The tower of shadow houses a divine gateway. A well-kept secret, it was, but… The gateway was once the birthplace of a god” (Elden Ring). Further into the game, however, the player must trigger a brief moment where Miquella seems to have shed his Great Rune—an object that is necessary for exercising his magical influence over the world—and gaining a new line of dialogue from Ansbach that illuminates how the charming effect may not be as benevolent as it once seemed: “Once, in an attempt to free Lord Mohg from his enchantment, I challenged Tender Miquella, only to have my own heart rather artfully stolen. I knew not how weak I was. I believed that with sufficient mastery, even an Empyrean would be within reach of my blade. I could not have been more mistaken… Miquella the Kind...is a monster. Pure and radiant, he wields love to shrive clean the hearts of men. There is nothing more terrifying” (Elden Ring). The player is faced with the realization that the devotion that Miquella’s followers have held for him has been compelled through a charm that the Empyrean has woven over them, rather than given freely as the followers had professed.

III. Pilgrimage

Pilgrimage sits in an important space both in the medieval period as well as in the world of Shadow of the Erdtree, the practice of following a path to commune at holy sites and sanctuaries formed and integral part of the experience of Christianity in the Middle Ages. One key aspect of the pilgrimage journey, the veneration of relics specifically, makes this practice interesting when brought side-by-side with its reinterpretation within Elden Ring. In his article “The Body in Medieval Spirituality” Matteo Salonia explores the connection between pilgrimage and the veneration of relics—remains of saints—suggesting “A fundamental principle underpinning medieval spirituality. . .is the dignity of the human body. In the mindset of Christian pilgrims in both Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, a crucial consequence of this principle was the body’s capacity to channel spiritual energy (e.g., performing miracles) even after death, once the soul had departed” (5). The importance of the physical flesh to spiritual custom is pointed to by this comment about Gregory the Great, “’plain reason’ was used by pope Gregory to conclude that the bodies of the dead would rise again, it seemed reasonable to him (and to the Christian faithful) that the bodies of martyrs and saints would perform miracles, precisely because such remains had not been forever separated from these holy persons” (Salonia 9). The flesh and spirit bound together by the Christian promise of the resurrection made saintly remains potent means for channeling their miraculous powers beyond the grave. Because of this, many medieval pilgrimages focused on the locations of these physical objects to determine the stops along their routes, with these paths following the relics if they were ever moved from one location to another (Salonia 10). Salonia adds, “In relation to pilgrimage, we could say that the suffering of a Christian martyr can be intended within Augustinian philosophy as a kairic moment, which repeats the kairic moment par excellence: Christ’s suffering on the cross. Hence, since time is intrinsically linked to space and physicality, a journey towards the mortal remains of a saint should be truly (not just symbolically) understood as a journey towards Mount Calvary” which points to the ways in which physical action and symbolic weight of pilgrimage act in tandem to create meaningful motion: “There cannot be salvation without a movement that is as much physical as spiritual, and that holy men are powerful—or, as Magli put it, “carriers of power” (Salonia 16).

Valarie Allen looks specifically to the roads and movement that take place during pilgrimage in her essay, “As the Crow Flies: Roads and Pilgrimage.” Her essay contrasting the road as a means to an end with the sense in which humans are “always on the move until reaching one’s eternal destination—and in that sense pilgrimage and the human condition are coterminous—the pilgrimage industry of the late Middle Ages, with its multiple shrines and hallowed places, capitalizes on the possibility of a contingently final destination on earth, a heaven attainable in the here and now” (Allen 33). Echoing the Augustinian philosophy mentioned by Salonia. She describes the nature of the roads in pilgrimage as “like the flow of blood around the body, the circulation of pilgrims around the roads through the realm was seen to carry the sanctity to the body politic,” emphasizing the importance of pilgrimage as an indicator of a healthy population (Allen 34). Conversely, then, it would be seen as stagnant for a lack of pilgrims to be seen on the road, showing the wickedness of the realm rather than its sanctity. Commenting on a moment from the Book of Margery Kempe, she notes how the narrative of pilgrimage itself is “as if being on the road was an end in itself” keeping in line with this Augustinian interest in the act of movement through pilgrimage is more than just the means to get to the next relic or holy site (Allen 34).

With the prominence of Pilgrimage as a practice comes maps dedicated to recording prominent sites to which people pilgrimage, especially in Jerusalem with its prominence in the Christian canon. Maps of pilgrimage also act as marks of who made them and what they value in a holy site, along with what their religious affiliation values as well (Rubin 268). In a comparison of three different maps of Jerusalem, Rehav Rubin points out that the three early modern maps used in his study—one "printed in Paris in 1687, in Latin, by a Catholic Franciscan friar. The second one was printed in Greek, by an Orthodox clergyman, in Venice in 1728. The third was printed in German, in Vienna, also in 1728”— also acknowledge the existence of biblical but non-locatable cities (268). “In. . .part of the sea four blazing bonfires are depicted, identified by captions as Sodom, Gomorrah, Adamah and Zeboim, the four cities, which were wiped of the face of the earth.30 It might be that the story of Sodom and Gomorrah was included not only as a geographical and historical feature but also as a lesson of reward and punishment” suggests that much like the practice of walking the pilgrimage paths the maps used to denote locations along those paths also served as more than a tool for locating oneself (Rubin 276). They also provided allegorical lessons through the use of anachronistic additions, acting not only as records of physical space, but also as conceptual documents that show the perceptions of their makers and how they valued different aspects of Jerusalem through which pilgrims would travel (Rubin 287).

Henny and Shalev note that travel of this kind was not limited to land travel, nor were Catholics only denomination to follow such paths. For seafaring pilgrims, which often traveled to Jerusalem from Italy, “The Mediterranean was in itself a sacred landscape that was navigated by seamen and passengers with the aid of shrines en route” (Henny and Shalev 804). Protestant pilgrims also found use in these pathways and the practice in general, “After the consolidation of the Reformation, there seems to have been nothing humiliating about recounting a sacred journey in one’s biography—quite the contrary: Protestant dignitaries invested themselves in the textual traditions of such accounts” (Henny and Shalev 818). These two groups that would normally not be seen as the typical pilgrim figure are also included in this ecosystem—both religious and financially— that developed around the routes.

In her essay on virtual pilgrimage, the internet-supplied perspective into distant places, Rodanthi Tzanelli compares religious and secular pilgrimage as “morphologically connected: they both look to the subject’s break from ordinary (profane) time; demand personal commitment or investment to an idea shaping the subject’s perception of the world; organize this perception with the help of ritualistic repetition of worshipping practices; and promise some sort of psychocultural transformation of one’s inner self from afar” (236). Her approach focuses on the pluralistic view that digital environments give to the physical places they represent. For example, digitally exploring Athens, Greece, through images, videos, and written descriptions will all produce different views of the city in the mind of the explorer “each of them valid in its own right” (Tzanelli 237). Analogous to its physical counterpart, this digital pilgrimage also produces a kind of culture and community that builds up around these internet pilgrimage routes, such as message boards, wiki articles, and commentators on blog and vlog platforms (Tzanelli 237).

IV. Saintly Precedent, St. Andreas

In addition to pilgrimage practices and culture being replicated in miniature within the Shadow of the Erdtree, we can also find precedent for Miquella’s actions in the realm of saintly narratives. The Old English verse Andreas from the Vercelli Book tells the story of St. Andrew as he travels to the land of Mermedonia to rescue his brother Matthew.

In the preface to the poem in his translation, Craig Williamson suggests the militaristic depiction of the saint as well by quoting Mary Clayton who suggests the tone of the adventure is closer to a secular heroic poem and “in this context conveys the sense of their being soldiers of Christ, milites Christi, with Andrew as their leader against the forces of the devil represented by the Mermedonians” (189). This sets the ground for an interesting comparison between a character within a combat focused video game, giving the context of military-like devotion to a holy figure, along with being set in a hostile country set firmly against outsiders in both cases (ll. 42-46). This more militant approach is pointed out as unusual by Samuel Cardwell in his essay on Andreas noting that “The use of the past participle of gebeodan in this warlike sense of ‘offering battle’ is rare in OE, only appearing here and in one line of Daniel; it more commonly has the sense of ‘command’, ‘ordain’ or, more neutrally, ‘offer’. The word geboden may be intended as an ironic reversal or perversion of God’s commandments on the part of the Mermedonians, who are only able to ‘offer’ or ‘command’ strife” (11-12). This interest in a more combative sense prevalent even before the passage marked out by Cardwell; “Soon I will send Andrew to sustain you, / your shield and solace in this heathen city. / He will save you from this nation’s terror, / this alien evil, this devouring hatred. / Andrew will arrive in twenty-seven nights, / and you will be freed from the vile unfaith / of those murdering Mermedonians. You will then pass / from suffering to salvation, from grim torture / to the glories of heaven, from the heart’s humiliation / to the comfort and keeping of the victorious lord” (ll. 115-124). Here we also see this language in the juxtaposition between humiliation and victory, implying them to be opposites as in earlier in the passage. In this sense, it is worth noting that the opposite of humiliation is not something more passive or self-centric, such as honor, revenge, or respite, but instead a word that more directly denotes dominion. This theme is even more explicit in God’s rescue of Andrew after his torturous walk through the desert: “Then the holy warrior, the beloved soldier, / looked back at the long track of his tears / As his God and Glory-king had commanded, / and saw beautiful, bright groves, blooming / with flowers everywhere his blood had fallen. / His gore had transformed the dead land / into God’s green grandeur, a garden of light” enforcing both an image of Andrew as a militant, but also as a bringer of abundance simultaneously (ll. 1492-1498).

Caldwell also suggests that “This at least raises the possibility that the poet—in all likelihood writing for a clerical audience— intended Andreas to serve as an encouragement and exemplum for those who were considering taking up ‘the missionary life’” which sheds an instructive light on the gruesomeness of the poem (23). Andreas, through this lens, becomes a kind of worst-case-scenario regarding the call to missionary work; “You must risk your life for the love of your lord” (ll. 226). This is most apparent in the description of the land of Mermedonia as the most inhospitable place that a missionary could possibly travel to and yet still would be able to make it back alive. Alexandra Bolintineanu points out that “from the very beginning it emphasizes the Mermedonians’ hostility to strangers, their monstrous eating habits, their alliance with the devil, even their geographical remoteness and isolation from the rest of the world” to summarize the negative qualities of the country (150). This maximization goes so far as to eschew the standard Christian imagery of bread and wine in favor of bread and water when indicating what material culture norms that the Mermedonians are without to more closely align with what would be familiar to a medieval English audience (Bolintineanu 152).

Speaking more broadly to the land of Mermedonia itself, outside of the country’s social practices, Bolintineanu also discusses the use of the word mearcland to describe the cannibal country as it “connotes otherworldly menace, as the use of borderlands in other Old English poems suggests: in Guthlac A, the word mearclond describes the saint’s demon-ridden hermitage (l. 174); in Beowulf, borderlands are the stalking ground of Grendel, the mære mearcstapa (mighty wanderer of the borders, ll. 103, 1348)” (154). This, along with the poet’s equation of the Mermedonian’s cannibalism, makes for an otherworldly, hellish environment for Matthew and Andrew to be trapped in (Bolintineanu 153). As Lindy Brady notes as well, the term borderland that is referenced in Andreas and Beowulf is also associated with the Welsh borderlands which “were a mixture of Anglo-Saxons and Welsh, and contemporary texts depicted the region as a highly distinctive place” (7). Brady uses the term Welsh borderland to “refer to this amorphous territory at the foot of the Cambrian mountains where the Anglo-Saxons of western Mercia and the Welsh of eastern Gwynedd and Powys came together” (8).

We see this otherworldly aspect especially clearly during the torture of St. Andrew, during which he is taunted for his faith: “Your savior was only a ghost on the gallows, / a corpse in an earth-cave, a ghoul underground” (ll. 1354-1355). Portraying the land as so barren and desolate that the people must resort to eating only each other sets the stage for the transformative intervention of both the landscape and the people. In the case of the landscape, it becomes clear that his blessings from God undermine the torture of the demons, transforming Andrew’s spilt blood into groves and plant life: “Then the holy warrior, the beloved soldier, / looked back at the long track of his tears / As his God and Glory-king had commanded, / and saw beautiful, bright groves, blooming / with flowers everywhere his blood had fallen. / His gore had transformed the dead land / into God’s green grandeur, a garden of light” (ll. 1492-1498). Even in this moment of transformation the description of St. Andrew is still that of a military figure, the Andreas-poet referring to him as a “holy warrior” and a “beloved soldier.” It is after this moment, once he is freed from his captors and has gained the upper hand that St. Andrew transforms the people: “Then Andrew began to gladden the hearts / of the waiting warriors with these words: / ‘fear not in this dark hour your own destruction, / even though those sinners are headed toward hell, / for the radiance of glory will reveal the truth / to those who realize and repent their crimes / and live mindfully in the Lord’s light’” (ll. 1651-1657).

V. Spatial Storytelling

When considering narratives interested in space, whether that space is literal, virtual, or physical, spatial storytelling theories become important to help analyze such location-specific practices. Narratologist Marie-Laure Ryan posits that the separation between space—a physical area—and place—a location with specificity and identity—is based on the stories and histories that are told about that place (86). We can see this distinction in video games very clearly, especially in Elden Ring, where the player traverses a mostly open environment. When the player transitions from the “space” of the open world to the “place” of the story that is intended to have deeper meanings and affective weight in the world, the name of that place appears on the screen for a moment with a deep resonant sound to signify its importance set apart from the rest of the game space. Being presented with the name of a place up front also happens in Andreas when the poet mentions Mermedonia: “Then Matthew came to that infamous city / of Mermedonia” (ll. 42-43). By the 2nd page of the poem in Williamson’s edition, well before being introduced to the titular character, the poet gives the reader the name of the city to separate it out from the rest of the “savage island” (ll. 17). These examples work as case studies for Ryan’s point that “the function of names is not to designate the properties of a certain object but to call its existence to the attention of the hearer, to impose it as discourse topic—in short, to conjure a presence to the mind” (89). Rather than simply listing all the feelings, thoughts, and symbolism that can be contained within the variety that generalized space can hold, the use of a name allows for all of these elements to be expressed from a single word or phrase. Laura Beiger argues that, on a broader scale, that “narratives exist and are meaningful only because they are situated in and across space, within networks of stories and trajectories, and with a distinct spatiality that is molded from the specific relations among all the actors (human, technological, and other) brought together in a particular network” and even that our language to describe storytelling is based in spatial language (15).

While both authors are writing about the way that space works in storytelling in book form, these discussions also illuminate the importance of applying narratological thinking to three-dimensional space. While Andreas works as a traditional text, travel takes a central role within the poem, as it does within the practice of pilgrimage which is facilitated by travel through space, and Elden Ring where it is necessary to move the player’s avatar through the virtual environment. Beiger calls into question how space interacts with media in a way that is helpful to think about in this context of travel and stories: “media are by definition spatial (as agents of transference, transportation, and transmission), while space is in and of itself a mediating practice (as it is an enabler of modes of transference, transportation, and transmission)” (19). This thinking relates to the earlier discussion of Augustinian interpretations of space along the pilgrimage paths, that movement within a narrative context has weight beyond the symbolic. She concludes her essay reflecting on how human existence and narrative is bound up in both space as well as time, bringing to mind the importance of time to the practice of pilgrimage (Beiger 24).

VI. Miquella, Pilgrimage, and Andreas Together

The reproduction of medieval sainthood in Shadow of the Erdtree can be tied to these two areas of medieval culture: depiction of saintly practice and pilgrimage culture. The character of Miquella interacts with both of these concepts as does the player as they explore the game environment seeking to find Miquella and prevent his apotheosis.

When the player gets to the entrance of the DLC, they are met by Needle Knight Leda, one of Miquella’s followers who is looking for the god-to-be who gives the inciting dialogue of the pilgrimage “Ahh, were you guided here by Kindly Miquella? I am Leda, and like you, I was guided by faith along his honorable path. Touch the withered arm, and you too will be transported. To the realm of shadow, where Miquella the Kind now dwells. My compatriots are there already. Like us, they have heard Kindly Miquella's call” (Elden Ring). What is notable here is that the group is described as being guided by faith, a key component of religious pilgrimage, that it is undertaken as a faithful act. In this case, the pilgrimage directly follows the crosses that mark the flesh shed along the path, as one of Leda’s notes states, “The Gate of Divinity lies in the tower sealed by shadow. That is surely where Kind Miquella is headed. We are no Empyreans, but we must locate the path that will lead us there. I will follow the crosses east” (Elden Ring). While, for practical reasons, the game does not actually portray Leda moving from cross to cross, the implication is still that of the character following in the footsteps of their leader. Additionally, this note is also a means of directing the player’s own pilgrimage from one cross to the next in a similar manner to the maps produced by Sir Ansbach, which act in a similar way to the pilgrimage maps discussed above: they facilitate visiting the sites where holy events (the shedding of Miquella’s worldly ties) have occurred. This pilgrimage acting as a group pilgrimage for the followers together.

Similar to Leda, Thiollier, has his own pilgrimage following the discarded pieces of Miquella that was left behind, “Would Kindly Miquella chasten me? For falling for St. Trina, while knowing that she was the discarded half? The problem is… I simply cannot help it. I would sacrifice everything, just to gaze upon her, one last time” (Elden Ring). In the context of his story the pilgrimage that he goes on is towards the discarded piece of Miquella is more closely analogous to the solo journey that Matthew sets out on than that of Andrew in Andreas. In his movement away from the rest of the group of followers, Thiollier gives an example of pilgrimage that is more focused on the individual attaining their goals rather than the collective pilgrimage that the rest of the characters go on. The only other person to follow Thiollier is the play themselves, who facilitates his journey as well as ends up being the one able to commune with St. Trina on his behalf.

Once the player has entered the Realm of Shadow, through pilgrimage to the crosses left by Miquella and bring the quests of the NPCs to the forefront, begin to gather Scadutree fragments and the player must “Consume these at sites of grace to bolster your Scadutree Blessing” (Elden Ring). By increasing their blessing, the player becomes more resistant to damage from enemies as well as able to deal more damage when they attack. Whereas the medieval pilgrimage symbolically strengthens the pilgrim’s faith, Shadow of the Erdtree makes this metaphor more literal. This growth and change over time can also be read in Andreas, where Andrew begins his journey unsure in his abilities to reach his destination, “how can I cross the sea / as quickly as you command? It’s surely easier / said than done! An angel might travel / with a touch of speed or a twist of time, / who knows the craft and curve of space, / the height of heaven, the breadth of seas, / but I cannot” (ll. 203-209). Analogous to the player’s growth in power, by the end of Andreas the saint is able to call a flood from a pillar to punish the Mermedonians (ll. 1545-1549) and even raise up those who had perished in the flood from the dead as baptized believers (ll.1658-1664).

It is in this moment of conversion that Andrew also shows the saintly power that Miquella reproduces with his charm: the ability to convert other people regardless of the circumstances. While he floods the country and drowns the people only to bring them back, this act of conversion is taken without question or grudge, and the poem ends with the Mermedonian’s exultation of God and veneration of Andrew, “Men brought / their beloved mentor, the brave warrior, / the best of men, to his ship on the strand, / watched him sail over the seal’s road / and slip silently beyond the sea’s horizon. Then they worshipped the God of Glory, / praising his power in one voice, saying, / “there is only one God, our holy Father, / The Lord and Creator of all living things, / Almighty, everlasting. His right and rule, / His promise and power, are glorious and blessed / All over middle-earth” (ll. 1763-1774). The dialogue of sea travel is mirrored as well in Miquella’s own dialogue during the final confrontation in the DLC when he charms the player, “"I promise you. A thousand-year voyage guided by compassion” (Elden Ring).

This compelled veneration, a standard feature of conversion stories, takes a more sinister twist when it is reinterpreted in Elden Ring, which can be seen in Ansbach’s dialogue of Miquella’s love as terrifying. Similar to the Mermedonians who are against Andrew, Shadow of the Erdtree introduces the character of Hornsent, a native to the shadow lands who harbors animosity towards the player and the gods for their conquest of the Realm of Shadow. As with the other characters, he is first met while under the influence of Miquella’s charm and his dialogue reflects the distrust that he harbors for the player that is only quelled by the compulsion, “Fie, another? Treading the heels of Miquella? Then, as that woman would surely say, we are in our purposes well aligned. But understand. Your kind are not forgiven. The Erdtree is my people's enemy. By Marika long betray'd, set aflame. I believe Miquella's apologies, when he says our delivery will come. But never will I see your kind as worthy” (Elden Ring). Once the charm is broken, however, and the player helps Hornsent defeat his enemy Messmer the Impaler, it becomes clear that without the charm there is no reason for him to want to follow along with Miquella’s plan, “To say the least, I am to you indebted. Yet unquenched remains my thirst for revenge. The death of Messmer was merely the start. Now comes the piper to collect from Marika, her offspring, and all the Erdtree's denizens... In vengeance for the flames, my blade I wield... If Miquella's redemption soothes the ache...that throbs within, demanding blessed vengeance... Then I wish not to be by him redeemed” (Elden Ring). Hornsent is not the only character whose benevolence is compelled either, as Needle Knight Leda who first guides the player is revealed to be murderously distrustful of others. Immediately when freed she says: “but while my devotion to Kindly Miquella remains unchanged, by my troth, I am not so sure about the others. No, wait. Perhaps this is a blessing in disguise. I can wield my sword to cull the undeserving, those unfit to bask in Miquella the Kind’s presence. I should’ve thought of this earlier” (Elden Ring). This is a realization that the player and Leda both arrive at, as indicated by her after killing Hornsent and eventually pursuing Sir Ansbach when she says: “I’ve come to a realization… There’s ample evidence… Without Kindly Miquella’s influence… I’m quite mistrustful of others…” (Elden Ring).

VII. Synthesis

Miquella acts as the reinterpretation of medieval sainthood in Shadow of the Erdtree, a status that is supported by his role as a divine redeemer for the characters within the DLC, as well as the relics that he shed along the path that the player must follow to reach their final confrontation. During his own religious pilgrimage, he lays the path for the rest of the cast and the player must undertake on their own pilgrimage to reach the divine gate where the player stops Miquella’s apotheosis so that they may achieve divinity in his stead, and it is through this pilgrimage that power is attained. It is this power of charm and conversion towards his goals that is present in the precedent of St. Andrew in the poem Andreas, yet Miquella’s use of conversion sheds a more complicated view on the practice. Rather than being met with absolute devotion and faith as in the case of Andreas, conversion in Shadow of the Erdtree is treated instead as a kind of subjugation that the player and the characters must resist in order to move forward. It’s through Miquella and his saint-like status within the game world that FromSoftware reinterprets and reworks the standard tropes of conversion, pilgrimage, and sainthood in the medieval literary legacy.

Bibliography

Allen, Valerie. “As the Crow Flies: Roads and Pilgrimage.” Essays in Medieval Studies 25, no. 1 (2008): 27–37.

Bieger, Laura. “Some Thoughts on the Spatial Forms and Practices of Storytelling.” Zeitschrift Für Anglistik Und Amerikanistik 64, no. 1 (January 1, 2016). 11-26.

Bolintineanu, Alexandra. “The Land of Mermedonia in the Old English Andreas.” Neophilologus 93, no. 1 (January 8, 2008): 149–64.

Brady, Lindy. Writing the Welsh Borderlands in Anglo-Saxon England. Manchester University Press, 2017.

Cardwell, Samuel. “‘Go Now’: Mission and Commission in the Old English Andreas.” Parergon 39, no. 1 (2022): 1–25.

FromSoftware Inc. Elden Ring: Shadow of the Erdtree. V. 1.16. BANDAI NAMCO Entertainment. PC/PlayStation 5. 2024.

Henny, Sundar, and Zur Shalev. “Jerusalem Reformed: Rethinking Early Modern Pilgrimage.” Renaissance Quarterly 75, no. 3 (2022): 796–848.

Robinson, Bradley, André Czauderna, and Sam von Gillern. “‘I Think I Get Why Y’all Do This Now’: Reckoning with Elden Ring’s Difficulty in an Online Affinity Space.” Games and Culture 0, no. 0 (2023): 1–19.

Rubin, Rehav. “One City, Different Views: A Comparative Study of Three Pilgrimage Maps of Jerusalem.” Journal of Historical Geography 32, no. 2 (April 2006): 267–90.

Ryan, Marie-Laure. Narrative as Virtual Reality 2: Revisiting Immersion and Interactivity in Literature and Electronic Media. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015.

Salonia, Matteo. “The Body in Medieval Spirituality: A Rationale for Pilgrimage and the Veneration of Relics.” Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion 14, no. 10 (2018): 1–21.

Tzanelli, Rodanthi. “Virtual Pilgrimage: An Irrealist Approach.” Tourism Culture & Communication 20, no. 4 (October 30, 2020): 235–40.

Williamson, Craig, trans. “Andreas: Andrew in the Country of the Cannibals.” In The Complete Old English Poems. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017.

Notes

[1] This is mentioned in multiple spots within the game, but specifically the description of the Bewitching Branch item, which states: “The Empyrean Miquella is loved by many people. Indeed, he has learned very well how to compel such affection.” All quotes from the game dialogue and item descriptions are sourced from Fextralife’s Elden Ring Wiki, which aggregates all the dialogue and can be found at https://eldenring.wiki.fextralife.com/.

Comments