“Plant Eyes on Our Brains”: A Speculative Reading of Bloodborne (2015) and Transhumanism

- Alex Heath

- Apr 5, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: May 7, 2025

Originally released just over a decade ago (at time of writing), FromSoftware’s standalone game Bloodborne (2015) for the PlayStation 4 may be considered one of the company’s most beloved entries in their soulsborne series of games, a subgenre which also includes Demon Souls (2009) and the Dark Souls trilogy (2011-2016). With its urban gothic environment, Lovecraftian themes, and the trademark oblique storytelling style of creative director Hidetaka Miyazaki the game has captured the minds of fans and scholars alike. Like the rest of the games in the soulsborne catalog, it presents its narrative differently to more traditional roleplaying games (RPGs). As opposed to giving the player exposition and direction through cutscenes and on-screen text outside of the diegesis of the game world as is customary in most games, Bloodborne presents its narrative almost exclusively within its diegesis, forcing the players to piece together bits of information from elements like notes around the game world, item descriptions, and character dialogue. [1]

It is, I think, this reluctance to relinquish information which captures the imagination of the audience of these games and has produced scholarship 10 years since its launch, a kind of “archeological mode of fandom” which Marco Caracciolo (2024) suggests (21). One aspect of this lore only skirted in Michaela Fikejzová and Martin Charvát’s 2024 essay on medical power represented in the game, and is more closely looked at in Aabir Sen’s work bringing Slavoj Žižek’s philosophy into the game world, is the transhumanist theme pervasive in the game world. In the description of Rom, the Vacuous Spider by another character, Micolash, he says, “as you once did for the vacuous Rom, grant us eyes, grant us eyes. Plant eyes on our brains, to cleanse our beastly idiocy,”[2] implying the college of Byrgenwerth which originally discovers the existence of great ones and eventually splintered into the other factions within the game sought to transcend the limitations of their humanity to be more like the Great Ones.

To this end I will be comparing activities the player undertakes and what they uncover in Bloodborne to the traditions of transhumanism both as a philosophical idea but also its modern posthuman aspects as pointed out by Allan Porter, “a structural analogy between—on the one hand—transhumanist conceptions of the human, the posthuman, and the relation between these, and—on the other—ancient conceptions of the human, the divine, and the relation between these” (2017, 242. Emphasis original). By addressing how transhumanism is acting within the world of Bloodborne, I hope to shed light on its value as a work of speculative fiction, providing a lens through which we can view the effects of transcendental ideologies.

Russell Belk (2020) writes on the subject of speculative fiction, treating the form as a means to discuss possible transhumanist and post humanist visions of the future, rather than as simple didactic narratives, asks us “to consider whether human nature is the same as posthuman nature or how the two might differ” rather than being biased for or against their themes (438). Treating Bloodborne as a piece of speculative fiction, then, it is important to consider a couple of views on transhumanism. Porter (2017) gives a definition of transhumanism from the transhumanist FAQ, citing, “The core of transhumanism is to encourage the use of biotransformative technologies1 in order to ‘enhance’ the human organism, with the ultimate aim being to modify the human organism so radically as to ‘overcome fundamental human limitations’” though he himself questions what fundamental limitations might look like in the context of bioethics (237-238).

“We are beginning to realize that even the most fortunate people are living far below capacity, and that most human beings develop not more than a small fraction of their potential mental and spiritual efficiency. The human race, in fact, is surrounded by a large area of unrealized possibilities, a challenge to the spirit of exploration,” wrote Julian Huxley in 1957 as he called for research to be done to push humans beyond the limitations of his time through scientific advancement (13-14). Additionally, he observes, “thanks to science, the under-privileged are coming to believe that no one need be underfed or chronically diseased, or deprived of the benefits of its technical and practical applications. The world’s unrest is largely due to this new belief” which presents the nature of science as a means of public good as a kind of chore meant to quell unrest, as he speaks of the “under privileged” as an outsider. The implication, then, is the privilege of the author.

While Huxley was writing a call to action for humanity to achieve the potential it has within it, Porter (2017), in his critique of transhumanist rhetoric, comments on the privileged nature of the position, noting “One may get the sense from such passages that transhumanists think that posthumans can ‘have it all,’ or even perhaps that ‘posthuman’ merely names a particular techno-fantasy of ‘having it all’—a life pervaded by pleasure and unsullied by suffering” (244-24). He sees the issue of the transhumanist impulse as a matter of values, certain values such as health, or happiness or even the notion of “better” cannot be applied flatly across all contexts in which they appear (Porter, 2017. 252-253).

The city of Yharnam, in which Bloodborne takes place, is ravaged by what the game calls a “beastly scourge,” where the denizens slowly become more bestial as they imbibe the blood distributed by the Healing Church. Blood, which was discovered by the collage of Byrgenwerth when they encountered a Great One, a Lovecraftian alien creature, in a vast labyrinth underneath the city. This “Old Blood thus functions as a pharmakon (Derrida, 1981), as a cure and a poison at the same time because, on the one hand, it allows for a certain period to cure human ailments and on the other hand it paves the way for the spread of the beastly scourge or the transformation of the human body into phantasmagorical forms” (Fikejzová and Charvát, 2024. 31. Emphasis original). Madelon Hoedt (2019) also points to the connection between the blood as a treatment and more ritualistic use— it is the Healing Church after all (37).

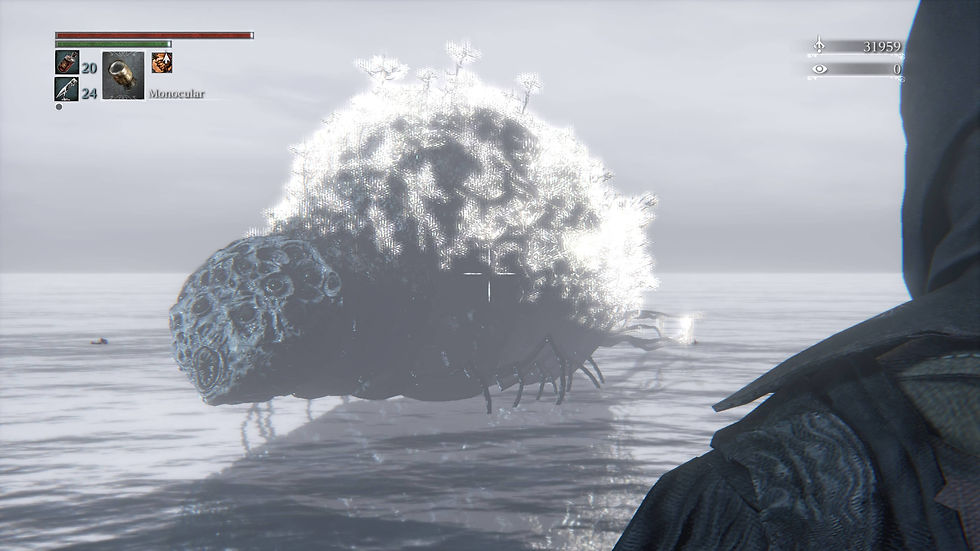

The player character is introduced to the situation in an opening cutscene, where they are given some “Yharnam blood of their own.” The first mention of transcendence the player finds is on a note in the very first room of the game, telling them to “seek paleblood to transcend the hunt.” Paleblood, though the player does not know when they read the note, refers to the creatures who possess pale blood, the Great Ones like Rom, the Vacuous Spider and Ebrietas, Daughter of the Cosmos, part of a godlike caste of entities of the world of Bloodborne (Hoedt, 2019. 72; Ford, 2024. 49). It is through these Great Ones transcendence makes itself a major element within the game’s narrative, as their blood becomes a medium with which the elite of the Healing Church, known as The Choir, conduct experiments to achieve a greater understanding of the Great Ones.

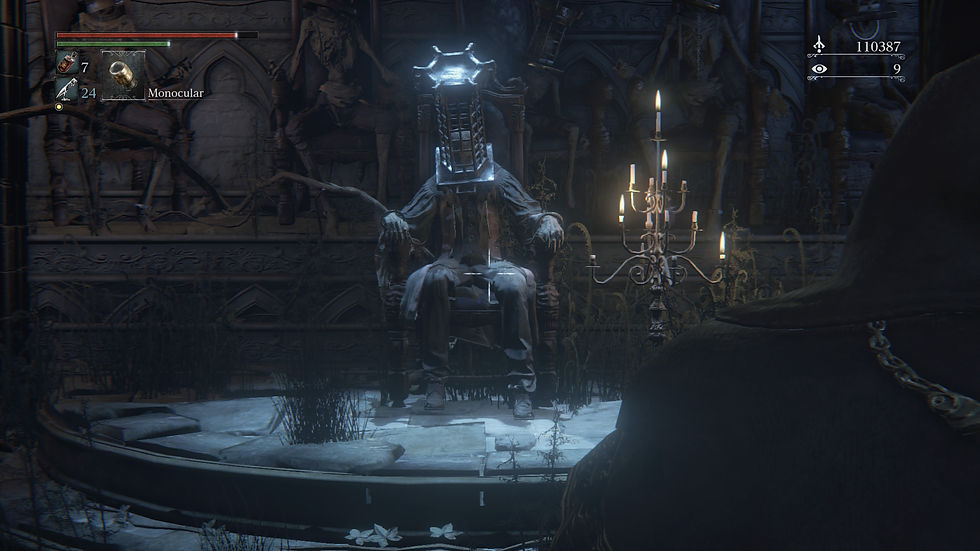

The other major faction the player encounters that is interested in a communion with the Great Ones is the Mensis School, a sect of scholars who broke away from Byrgenwerth in an attempt to commune with the great ones on their own. The player encounters them in the area of Yahar’Gul, Unseen Village, where they devised a ritual to enter the Nightmare Realm using special Mensis cages. The description of the cages themselves shed light on the goals of the school itself: “This hexagonal iron cage suggests their strange ways. The cage is a device that restrains the will of the self, allowing one to see the profane world for what it is. It also serves as an antenna that facilitates contact with the Great Ones of the dream. But to an observer, the iron cage appears to be precisely what delivered them to their harrowing nightmare.” Whereas the Choir sought understanding through Ebrietas, Micolash and the Mensis School he leads both aim for direct contact with the Great Ones.

What makes Bloodborne an example of transhumanism are the ways in which the Yharnamites act in response to the revelation of these Lovecraftian entities. Sen (2024) points out, “The elusive nature of these gods [Great Ones] grounds the idea that there is something that always escapes the rational mind, reiterating the Kantian notion of the ever-elusive noumenal world” (421). In other words, while the theories of the noumenal and phenomenal worlds discussed by Kant and Lacan remain theoretical in reality, they become literal in the world of Bloodborne, with its denizens forced to navigate with the knowledge that there are noumenal creatures which remain unknowable to them yet influence the world around them. It is the discovery of this noumenal reality that prompts the advancement of transhuman ideals within the world of Bloodborne rather than the technological ones at work in the world outside of the game. This discovery led to the two main factions pushing for evolution in two different directions both with disastrous ends.

For the Healing Church, the path to transcendence lies in blood ministration, “The Healing Church, led by Master Willem . . . sought to gain secret knowledge, and its goal became to push further the evolution of humanity, the expansion of human intellect and communication across space and time with cosmic beings” (Fikejzová and Charvát, 2024. 31). This ultimately leads to the beastly scourge the player must fight their way through, making up the mechanics of the game.

For the Mensis School, on the other hand, the path to transcendence lies in direct communion and existence within the Nightmare Frontier, an extra-physical space where the school resides. Facilitated by the use of the Mensis Cages, as noted above, allowing them to commune with an infant Great One named Mergo, as the One Third of Umbilical Cord dropped by Mergo’s Wet Nurse description reads, “Every Great One loses its child, and then yearns for a surrogate. This Cord granted Mensis audience with Mergo, but resulted in the stillbirth of their brains.” The stillbirth of their brains meaning the death of the entire school, who can be seen all throughout the area of Yahar’Gul seated in chairs with cages on their heads, left as desiccated corpses.

For the Player, though, this apotheosis is achievable, unlike any other character in the game. Should they find three of the four One Third of Umbilical Cord items and consume them before fighting the final boss, Gherman, an extra final boss will unlock, the Moon Presence. Once the moon presence has been defeated, a cutscene will play in which the player is revealed to have turned into a strange baby squid creature, transcending their human form and reaching the status of Great One.

This final ending provides a positive example that presents a nuance to the otherwise disastrous tales of becoming more-than-human presented by the rest of the narrative of Bloodborne. While for everyone else the tale of transcendence ends in death, the player is allowed to live on in what is considered by many players to be the true ending of the game. Ironically, an ending that is isolated, as opposed to Huxley and Porter’s preoccupations with mass transhumanism.

While establishing a connection between transhumanist themes and Bloodborne there is more to say on the topic, and I have just scratched the surface of both this complex ideology and complex narrative.

Footnotes

[1] All screen shots from Bloodborne were taken by the author.

[2] All in-game quote transcriptions are sourced from https://bloodborne.wiki.fextralife.com/ as Fextralife is the most up to date digital archive of this game and most others in the FromSoftware catalogue.

Bibliography

Belk, R. (2022). Transhumanism in speculative fiction. Journal of Marketing Management, 38(5-6), 1–20.

Caracciolo, M. (2024). On Soulsring Worlds. Routledge.

Fikejzová, M., & Charvát, M. (2024). The medicalisation and dissemination of cosmic horror in bloodborne. Acta Ludologica, 7(2), 26–37.

Ford, D. (2024). Approaching FromSoftware’s souls games as myth. Transactions of the Digital Games Research Association, 6(3), 31–66.

FromSoftware. (2015). Bloodborne. Bandai Namco.

Hoedt, M. (2019). Narrative Design and Authorship in Bloodborne: an Analysis of the Horror Videogame. McFarland & Company, Inc.

Huxley, J. (2015). Transhumanism. Ethics in Progress, 6(1), 12–16.

Porter, A. (2017). Bioethics and Transhumanism. The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy: A Forum for Bioethics and Philosophy of Medicine, 42(3), 237–260.

Sen, A. (2024). “We’re all mad here!”: Becoming god in Bloodborne. Games and Culture, 19(4), 419–432.

Further Reading

Dooghan, D. M. (2025). Fantasies of Adequacy: Mythologies of Capital in Dark Souls. Games and Culture, 20(2), 151–170.

Kirkland, E. (2009). Storytelling in survival horror video games. Horror Video Games: Essays on the Fusion of Fear and Play, 62–78.

Kocurek, C. A. (2015). Who hearkens to the monster’s scream? Death, violence and the veil of the monstrous in video games. Visual Studies, 30(1), 79–89.

Comments