Nosferatu (2024) Film Review

- Alex Heath

- May 8, 2025

- 4 min read

Over this weekend I finally got around to watching Nosferatu by Robert Eggers after missing it in the theaters last December. The season was just too hectic with finals and papers, plus living in Midtown Detroit puts the nearest popular film theater 10 miles away—too far away without a car. I really wanted to see it, too! I enjoyed watching The Lighthouse (Eggers, 2019), which I found somewhat comedic though impressive in its symbolist stylings and eerie seascapes, and I’ve received recommendations from just about everyone to see The Witch (2015) as I’ve achieved the goth friend status. I also had the great fortune to take a class in my last year of my master’s program at Wayne State University devoted entirely to the vampire film and the tropes and culture of them right before the professor who taught that class retired. If there is any kind of film that I would consider myself a specialist in, it would be vampire films. All of this to say, there has never been a film more pitched directly to me than Nosferatu.

The film itself is based on both the 1897 Dracula novel by Bram Stoker, as well as the 1922 silent film Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror directed by F. W. Murnau. The original film is, as of writing, the oldest surviving vampire film, and was originally made as a legally distinct adaptation of Dracula, leading to some of the design choices such as the name changes and the alterations to the cast of characters from a team of monster hunting companions who slay Dracula on his way back to his castle to the final death of the vampire coming at the sacrifice of Ellen Hutter (Read: Mina Harker) at the end of the movie. The 1922 film is also marked by a German Expressionist style, which allows for the vampire to look less human without the characters seeming to notice, as the audience recognizes that there is a level of symbolic depiction in the long ears and nails of Count Orlok (Read: Dracula). While familiarity with the source materials is not a requirement for the viewer, Eggers’ Nosferatu being a standalone film, I found that while watching it with my boyfriend that his attention often turned to me when Eggers’ scenes grew too dense, hoping that I would be able to enlighten him as to what was going on.

In Egger’s Nosferatu the beginning begins with a dream sequence (something that the film will make liberal use of, similar to The Lighthouse) where we see Ellen Hutter (Lily-Rose Depp) wandering in a garden as if sleepwalking, before collapsing and spasming and moaning on the ground. This marks the biggest change between the source material and the film: Ellen reached out and gained a psychic connection to Count Orlok (Bill Skarsgård) before the main story, unlike in the original or Dracula where Ellen is discovered by the Count because of a locket of her that Thomas Hutter keeps on his person. What this means is that Ellen’s character falls into a trope of Sybil-like female characters in the ilk of Vanessa Ives from Penny Dreadful (2014-2016) and Emma Wintertowne from Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell (2015), both characters with supernatural connections who are distrusted and given unhelpful medical treatment because they are not believed when they try and draw attention to supernatural dangers. With this change in how Ellen’s character is presented, Depp portrays this through physical acting reminiscent of Linda Blair in The Exorcist (1973) in order to show seizures and rapid changes in demeanor and temperament. While this haunted-style character works very well in the two examples previously, which have the benefit of being drawn out over the course of several hours of TV, Ellen’s story is not given enough breathing room in the 132-minute runtime. Because of this limited time frame with which to communicate the rules of how this version of the vampire story will work, Ellen’s story often appears to compete against the other events going on in the film. No more is this the case than near the two thirds mark when Ellen confronts Thomas Hutter (Nicholas Hoult) about Count Orlok and the chaotic scene culminates with the pair having sex in some act of defiance against the Count, though this is never really returned to nor shown to have any consequences in the final act of the film.

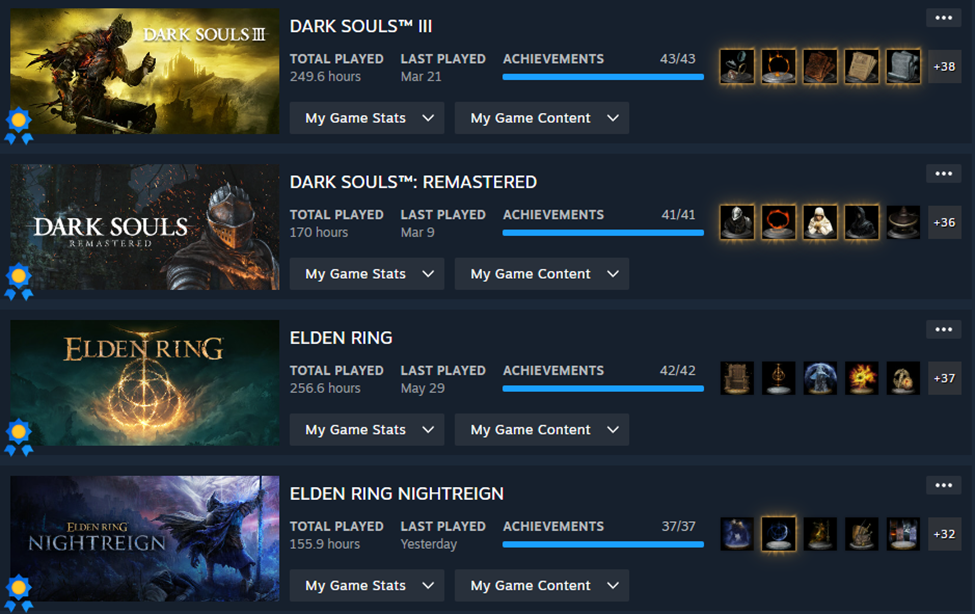

I really enjoyed the atmosphere of some of the shots, especially Thomas getting on the unmanned carriage that reminded me immediately of the departure scene in Bloodborne (FromSoftware, 2015) when the player leaves Yharnam for Forsaken Castle Cainhurst. The washed-out color palate adds to the antiquated feel of the film and the misty, dreamlike haze that permeates many of the scenes. While I enjoyed this, I think it also makes more prominent the biggest issue with the movie: unreality. Much of the film it is unclear what of the activities are really happening and which are dreams, much like in the scenes where Ellen acts possessed; it is unclear whether this is something that is going on with her character, possession of a spirit, or Count Orlok exerting some influence, with the later seeming to never be the case since Skarsgård plays his Orlok as a contemplative and slowly dominating noble. While Eggers’ films are known for a strict adherence to historical reality, the town of Wisburg that the movie takes place in is a fictional German port town, where no reality can really take hold, and by extension there are no rules for the viewer to ground themselves with.

Overall, I was somewhat disappointed with the story getting lost in its own dream-like conceit, especially as such a fan of the source novel and the vampire film as a genre. I think my favorite part of the film had to be the one deliberate reference to Dracula when Herr Knock (Simon McBurney) is strapped into an electric chair and finally wails the iconic line “the blood is the life!” before tearing out the jugular of the orderly strapping him in place. Beyond that reference, which has been made comical to me after Dracula Unleashed (an old PC point and click adventure game from 1993), I thought that the film struggled to clear its own mists and make clear the establishing action.

Comments